Prevalence of Adverse Analytical Findings (AAF) Among Athletes in Kuwait (2022-2023): Results from the Kuwait Antidoping Program

Abstract

Background: Doping, or the use of prohibited substances, poses a significant challenge to the sports field, leading to violations of the principle of fair competition. The study aims to investigate the prevalence of prohibited substances and methods among athletes, identify the prohibited substances and their classifications used, and provide future recommendations for enhancing optimal sports performance.

Method: A cross-sectional study utilized data extracted from the WADA Anti-Doping ADAMS platform. All samples collected pertain to athletes registered with various national sports clubs and federations in Kuwait from May 1, 2022, to December 31, 2023.

Result: Out of 667 samples, 3.4% of the total samples exhibited AAFs violation, whereas 96.5% yielded NR for doping. Most of the athletes in both groups are young adults aged 16 years to less than 30 years old, male, and Kuwaiti. There is no statistically significant difference in the preval ence of AAF samples according to demographic characteristics, sport category, or disciplines. (p values>0.05).

Keywords

Prevalence • Prohibited substance • Prohibited method • Sport • Wada • Aaf

Abbreviations

AAF: Adverse Analytical Findings; AAS: Anabolic Androgenic Steroids; ABP: Athlete Blood Passport; ADAMS: The Administration And Management System Platform; ADRV: Anti-Doping Rule Violation; ANOVA: One-Way Analysis Of Variance; ATF: Atypical Finding Results; CNS: Central Nervous System; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; DCOs: Doping Control Officers; EPO: Erythropoietin; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; KADA: Kuwait Anti-Doping Agency; NR: Negative Result; QADL: Qatar Anti-Doping Laboratory; RTP: Registered Testing Pool; THC: Tetrahydrocannabinol; TP: Testing Pool TUE: Therapeutic Use Exemption; WADA: World Anti-Doping Agency; UNESCO: The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

Introduction

Doping, or the use of prohibited substances, poses a significant challenge to the sports field, leading to violations of the principle of fair competition. Since its inception in 1999, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has adopted an international code for doping and established international standards to safeguard athletes’ fundamental right to compete in a doping-free environment while ensuring the coordination and efficacy of anti-doping programs at both international and national levels. The first WADA international code was adopted in 2003. The agency defines a prohibited substance or method as a substance or method that meets any two of the following three criteria: (1) it has the potential to enhance sports performance, (2) it represents an actual or potential health risk to the athlete, and (3) it violates the spirit of sport [1]. WADA establishes a prohibited list that is revised and updated annually by the Prohibited List Expert Advisory Group, based on modifications to prohibited substances used worldwide [2].

In April 2024, WADA released the 2022 Antidoping Testing Figures, indicating a rise in the prevalence of Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs), which are sample reports that investigate the presence of prohibited substances or prohibited methods, from 2021 to 2022. In 2021, the AAF proportion constituted around 0.65% of total samples collected for the year, and it increased to 0.77% in 2022 [3]. Understanding the actual prevalence of doping is crucial for the development and implementation of successful antidoping programs and for evaluating their efficacy [4].

Kuwait officially endorsed the Copenhagen Declaration and ratified the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) International Convention against Doping in Sport on May 30, 2007. This commitment corresponds with Kuwait’s persistent endeavors to eliminate doping in sports, emphasizing a political and ethical framework to promote fair competition [5]. After numerous years of productive endeavors, the Kuwait Anti-Doping Agency (KADA) was formally founded in 2021 by the enactment of Law 82/2018 as a national organization to combat doping in Kuwait. According to paragraph 20-5-1 of the World Anti-Doping Code, KADA has the requisite authority and responsibility for autonomy in its decision-making and operational functions related to sports and governmental entities. Among other things, this means making sure that no one who works for or manages an international, national, or organization for sporting events, or any national Olympic committee, national Paralympic committee, or government agency in charge of sports or anti-doping can have any effect on the organization's decisions. KADA is tasked with the development, establishment, implementation, monitoring, and enhancement of the doping control program in Kuwait [6].

Due to the absence of data concerning the prevalence of prohibited substances and methods of detection among athletes in Kuwait, it is essential to identify it in order to enhance and update the national anti- doping program. The study aims to investigate the prevalence of prohibited substances and methods among athletes, which is presented as a percentage of AAFs in collected analysed samples. In addition, it evaluates the prevalence of AAF according to age category, gender, sport, nationality, competition setting, and sample type and identifies the predominant prohibited substances in AAF samples. Finally, the study offers future recommendations to enhance the national anti-doping program in order to achieve optimal sports performance.

Method

Study design and data extraction

A cross-sectional study was conducted using data extracted from the WADA - Administration and Management System (ADAMS) platform with the ethical approval of KADA administration. The informed consent to participate was not needed for this study. The collected data encompassed sample code, type of sample, sport category, discipline, gender, age, nationality, competition status, granting of Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE) by the athlete, and test result. Additionally, data about the prohibited substances or their different metabolites, classification, and methods were also collected. Fifty-five Doping Control Officers (DCOs) supervised the sample collection processes by conducting 492 official visits over two years. The Qatar Anti-Doping Laboratory (QADL) analyzed the test samples in accordance with an international contract between Kuwait and Qatar. The confidentiality of athletes’ names was maintained during data collection from the ADAMS platform. Data was incorporated for samples collected from May 1, 2022, to December 31, 2023.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria are athletes who are registered with various national sports clubs and federations in Kuwait, which are currently estimated to be approximately 19 national federations, 34 sporting clubs, and 31 specialized clubs and committees. In addition, athletes, who are 16 years of age or older, and both genders are included. Kuwait classifies sports into individual and team categories. The individual sports featured are 21: aquatics, athletics, boxing, bowling, canoeing, cycling, fencing, electronic sports, judo, and karate. Additionally, the list encompasses kickboxing, powerlifting, rowing, and sailing, shooting, squash, taekwondo, table tennis, tennis, weightlifting, and wrestling. The six team sports represented are basketball, football, handball, ice hockey, padel, and volleyball. Athletes who are enrolled in the Registered Testing Pool (RTP) or Testing Pool (TP) in the national antidoping control program are also incorporated in the study. However, the study excluded Atypical Finding Results (ATF) and other Anti- Doping Rule Violations (ADRV).

Statistical analysis

This study investigates the demographic characteristics of the analyzed samples by stratifying them by athlete's age category, gender, nationality, competition setting, sample type, and sport category. The study provided an overview of the prevalence of prohibited substances and methods of usage among athletes in Kuwait, which is represented by the percentage of AAF among the analyzed sample. IBM SPSS (Version 26®) performed the statistical analysis, using basic descriptive statistics to summarize the data by frequencies and percentages. Categorical and ordinal variables were analyzed using the chi- square test, specifically the demographic characteristics and the Prevalence of Normal Results (NR) and AAF. Age was categorized into three categories: (1) 16 years old to less than 30 years, (2) 30 years to under 40 years, and (3) 40 years and older, allowing for structured analysis of age-related trends. The associations between the prevalence of NR and AAF based on demographic characteristics were considered statistically significant with a p-value less than 0.05.

Results

Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic characteristics of the analyzed samples for 667 athletes. The largest age group of the sample included athletes aged between 16 and less than 30 years old (69.4%), followed by 30 to less than 40 years old (29.2%), with a very small percentage (1.34%) of participants aged 40 years or older. The majority of athletes were males, with 90.2%, and 9.8% were female. Nearly 91.2% of the athletes were Kuwaitis, with the remaining 8.8% representing various nationalities such as Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, the Syrian Arab Republic, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Tunisia. Additionally, other nationalities, including Somalia, Iran, Korea, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Sweden, Bosnia, and Herzegovina. The Russian Federation, Jamaica, the United States of America, Colombia, Libya, Serbia, France, Nigeria, Montenegro, and Ghana were also enclosed. In the context of competition, we obtained around 60.4% of samples in an in-competition setting and the remaining 39.6% in an out-competition setting. The total number of samples collected is nearly equivalent between individual and team sports (54.2% vs. 45.7%). Lastly, three types of sample tests, including blood, urine, and Athletic Blood Passport (ABP), were enclosed in the study, and around 94.4% of samples collected were urine samples.

| Item | Sub | Total (n=667) 100% |

|---|---|---|

| Athletes’ Age (years) | 16 - ˂30 years | 463 (69.4%) |

| 30 - ˂40 years | 195 (29.2%) | |

| 40 years and more | 9 (1.34%) | |

| Gender | Male | 602 (90.2%) |

| Female | 65 (9.8%) | |

| Nationally | Kuwaiti | 608 (91.2%) |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 59 (8.8%) | |

| Competition setting | In | 403 (60.4%) |

| Out | 264 (39.6%) | |

| Sample type | Blood | 19 (2.8%) |

| Urine | 629 (94.3%) | |

| ABP | 19 (2.8%) | |

| Sport category | Individual sport | 362 (54.3%) |

| Team sport | 305 (47.1%) | |

| Sample result | Normal Result (NR) | 644 (96.6%) |

| Advance Analytical Finding (AAF) | 23(3.4%) |

Table 2 represents the prevalence of Normal Results (NR) and Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) according to demographic characteristics. The frequencies of age groups, gender, nationality, competition level, sample type, and sport category were comparable between both groups, and the p-value is calculated using the Chi-square test. Overall, 3.4% of the total samples exhibited AAF violations, whereas 96.5% yielded Negative Results (NR) for doping. All AAF violations resulted from the presence of prohibited substances in the analyzed samples, with no detection of prohibited methods. Most of the athletes in both groups are young adults aged 16 years to less than 30 year’s old, male, and Kuwaiti. Urine samples were the most common, and more athletes participated in individual sports. All samples are collected similarly in our competition setting. Regarding the demographic characteristics of AAF samples, 20 of these samples (87.0%) were collected from Kuwaiti athletes, and only 3 samples (13.0%) were collected from other nationalities. Moreover, both competition settings presented almost similar numbers and percentages of AAFs (56.5% in the in-competition setting and 45.5% in the out-of- competition setting). According to the sport category, 15 AAF samples (65.2%) were identified in the individual sports category, while 8 AAF samples (34.8%) were identified in the team sports category. There is no statistically significant difference in prevalence of AAF samples according to demographic characteristics (p values >0.05).

| Item | Sub | NR (N=644) |

AAF (N= 23) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athletes’ Age | 16 - ˂30 years | 447 (69.4%) | 16 (69.6%) | 0.780 |

| 30 - ˂40 years | 188 (29.3%) | 7 (30.4%) | ||

| 40 years and more | 9 (1.4%) | 0 | ||

| Gender | Male | 580 (90.1%) | 22 (95.7%) | 0.374 |

| Female | 64 (9.9%) | 1 (4.3%) | ||

| Nationally | Kuwaiti | 588 (91.3%) | 20 (87.0%) | 0.471 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 56 (8.7%) | 3 (13.0%) | ||

| Competition setting | In | 390 (60.5%) | 13 (56.5%) | 0.697 |

| Out | 254 (39.5%) | 10 (45.5%) | ||

| Sample type | Blood | 18 (2.85) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.647 |

| Urine | 607 (94.3%) | 22 (95.7%) | ||

| ABP | 19 (3%) | 0 | ||

| Sport category | Individual sport | 347 (53.9%) | 15 (65.2%) | 0.284 |

| Team sport | 297 (46.1%) | 8 (34.8%) |

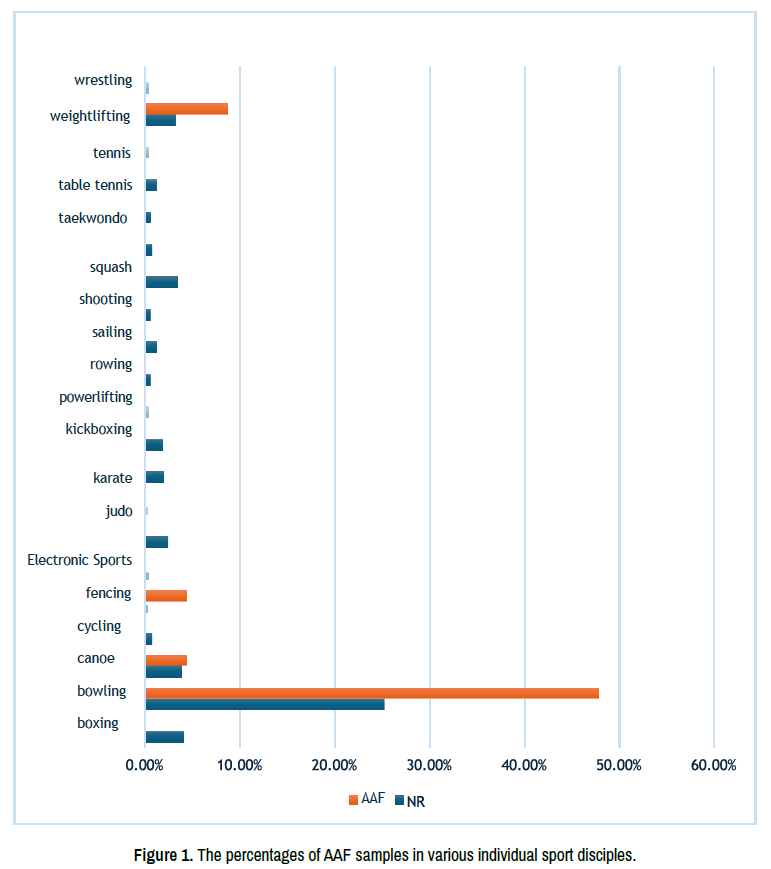

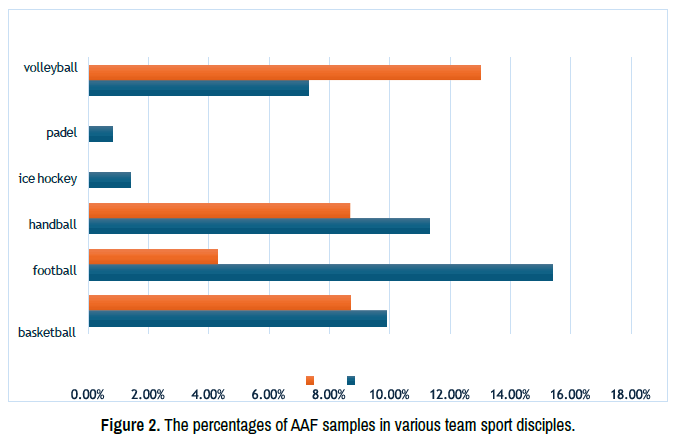

Figure 1 illustrates the percentages of AAF samples in various individual sport disciplines, while Figure 2 illustrates the percentages of AAF samples in various team sport disciplines.

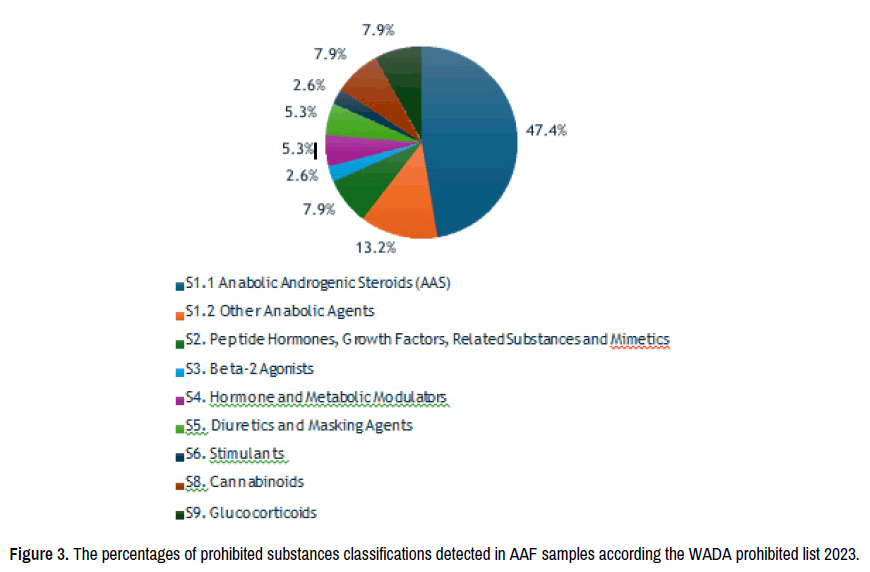

Table 3 presents the list of prohibited substances detected and their classifications according to the WADA prohibited list 2023. However, the analyzed AAF samples did not detect S0 non-approved substances, M1-3 prohibited methods, S7 narcotics, or P1 beta-blockers. Out of a total of 23 AAF samples, 14 samples (60.8%) detected only one prohibited substance. However, 7 AAF samples (30.4%) detected two prohibited substances. Only one AAF sample (4.34%) detected three prohibited substances, whereas another AAF sample detected (4.34%) eleven prohibited substances from different classes. IIn 2023, only two athletes received TUE retroactively following the violation. Figure 3 illustrates the percentages of prohibited substances classifications detected in AAF samples according to the WADA prohibited list 2023.

| Type of Sport | Test Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Sports | Disciple | NR | AAF |

| Aquatics | 27 (4.2%) | - | |

| Athletics | 163 (25.3%) | 11 (47.8%) | |

| Boxing | 25 (3.9%) | 1 (4.3%) | |

| Bowling | 5 (0.8%) | - | |

| Canoe | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (4.3%) | |

| Cycling | 2 (0.3%) | - | |

| Fencing | 16 (2.5%) | - | |

| Electronic Sports | 1 (0.2%) | - | |

| Team Sports | Judo | 12 (1.9%) | - |

| Karate | 13 (2%) | - | |

| Kickboxing | 2 (0.3%) | - | |

| Powerlifting | 4 (0.6%) | - | |

| Rowing | 8 (1.2%) | - | |

| Sailing | 4 (0.6%) | - | |

| Shooting | 22 (3.4%) | - | |

| Squash | 5 (0.8%) | - | |

| Taekwondo | 3 (0.5%) | - | |

| Table tennis | 8 (1.2%) | - | |

| Tennis | 2 (0.3%) | - | |

| Weightlifting | 21 (3.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| Wrestling | 2 (0.3%) | - | |

| Disciple | NR | AAF | |

| Basketball | 64 (9.9%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| Football | 99 (15.4%) | 1 (4.3%) | |

| Handball | 73 (11.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| Ice hockey | 9 (1.4%) | - | |

| Padel | 5 (0.8%) | - | |

| Volleyball | 47 (7.3%) | 3 (13%) | |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to present an overview about the prevalence of prohibited substance usage among athletes in Kuwait. This research investigates the demographic characteristics of all analytical samples related to the athlete's age category, gender, nationality, competition setting, sample type, and sport category.

The main result of the study indicates that the prevalence of prohibited substance usage among athletes is represented as the percentage of AAF among the analyzed sample, and it is 3.4%. This prevalence correlates with the prevalences in other regional countries. A study showed that the prevalence of AAFs among Saudi athletes from 2009 to 2018 was approximately 2.24% [7]. Another study reported the prevalence of AAFs among French athletes in 2019 to be between 1.42% and 1.81% [8]. Additionally, research revealed that the AAFs prevalence among Italian athletes in 2009 was around 1.8% [9]. Recently, in 2024, a cross-sectional study conducted in the United States of America (USA) found that the prevalence of athletes testing positive for one or more prohibited substances ranged from 6.5% to 9.2% [4].

National and international doping agencies exert significant efforts to determine the prevalence of doping in order to assess their doping control programs. Despite these endeavors, the actual prevalence of doping globally remains uncertain due to the impact of numerous factors. Although there was no significant difference found in the prevalence of AAF according to age category, the results showed that the age category from 16 years to under 30 years old had a high percentage of AAF samples, which is justifiable for this age category. Numerous studies have elucidated the motivations for doping among the young age group, summarizing them as follows: (1) A strong desire to succeed in athletic competitions, (2) a propensity for experimenting with new supplements or substances to enhance performance, (3) insufficient life experience, and (4) a low educational level are the factors that have been summarized in numerous studies.4 Moreover, the second factor is gender, with no significant difference observed with the prevalence of prohibited substances in the study. Given that the samples collected in the study for male athletes constitute 90.2% compared to 9.8% for female athletes, it is reasonable to observe a higher prevalence of AAFs in male athletes than in female athletes. However, this does not imply an absence of doping practices among female athletes. Athletes of both genders purpose doping to enhance their performance.

Both genders use various prohibited substances or methods due to physiological and psychological disparities [8]. Several global studies investigated the usage of prohibited substances by female athletes. A study showed a significant difference in prohibited substance class utilization due to gender reported for some substances. Indeed, female athletes had a lower rate of use of prohibited substances under classes S1, S4, and S8, which include anabolic agents, hormone and metabolic modulators, and cannabinoids. On the other hand, they used more illegal drugs from classes S3, S5, and S9, like diuretics, glucocorticoids, and beta-2 agonists [8,9]. The third factor that may influence the prevalence of AAFs is athletes’ nationality. The study analyzed the prevalence of AAFs according to nationality, using samples from Kuwaiti athletes and other athletes from 30 different nationalities to evaluate variations in prohibited substance practices among them. The analysis revealed no significant difference. Evidence indicates that socioeconomic factors can influence doping practices among athletes, varying according to their features in each country [10]. Competition statuses are the fourth factor that may affect AAF prevalence. The study found no significant difference in the prevalence of AAFs in and out of competition. A study in Saudi Arabia indicated that the prevalence of positive samples was significantly higher among in-competition-setting athletes compared to those in out-of-competition settings [7]. The fifth factor is the sport category, which did not report any significant difference in the prevalence of AAF. The results revealed that individual sports, such as athletics, account for 47.8% of AAFs, while weightlifting accounts for 8.7%. In contrast, the prevalence of AAF in team sports is minimal, with volleyball accounting for 13% and basketball and handball representing 8.7% each. These results parallel the global doping spectrum based on the sport category. A study investigated that the relevance of doping among individuals and power sports is greater than in team sports [10]. Another study indicated that the proportion of AAFs in individual sports is elevated in cycling, boxing, and weightlifting. In addition, the proportions of AAFs in team sports were elevated in basketball and ice hockey [11]. The last factor is sample type, which showed no significant difference in the prevalence of AAFs, as many samples were urine samples.

Biological testing alone is not enough to find all prohibited substances and methods because the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of new substances change. This is why it is important to come up with and use new detection methods and tests in doping testing [3,12]. Future researches should persist in assessing the prevalence of AAFs based on all the above-mentioned factors.

The prohibited substances detected in AAF samples were classified according to the WADA prohibited list 2023.2 Statistical analysis revealed that all prohibited substance classes were present in the AAF analysis samples, with the exception of the following classes: S0 non-approved substances, S7 narcotics, P1 beta-2 agonists, and M1-3 prohibited methods, which are not detected. Regarding the quantity of prohibited substances that were identified in each AAF sample, 60.8% of AAF samples detected only one prohibited substance, which is frequently observed. Furthermore, we detected eleven prohibited substances in a single AAF sample, mixed from the S1.1 and S1.2 prohibited substance classes. This is the first time we have detected multiple prohibited substances in a single AAF sample. The following is concise information regarding each class of prohibited substances and their prevalence. It clearly showed that around half of the AAF-identified banned substances were classified under S1.1 AAS. A study was conducted. Investigators in Saudi Arabia found that anabolic steroids were present in 32.8% of the 141 positive urine samples [13,14]. Previous cross-sectional survey studies in regional countries have corroborated these results (Table 4).

| Prohibited Substances Classifications | No. of Samples Detected the Prohibited Substances |

Prohibited Substances |

|---|---|---|

| S1.1 AAS | 18 (47.4%) | Metenolone, drostanolone, boldenone, Nandrolone(19- nortestosterone), oxandrolone, metandienone, 1- testosterone |

| S1.2 other Anabolic agents | 5 (13.2%) | SARMS enobosarm (ostarine), SARMSRAD140, SARMS LGD-4033(ligandrol)SARMS S4 (andarine), clenbuterol |

| S2. Peptide hormones. Growth factors, related substances and mimetics |

3 (7.9%) | EPO |

| S3. Beta-2 agonists | 1 (2.6%) | Terbutaline |

| S4. Hormone and metabolic modulators |

2 (5.3%) | Meldonium, letrozole |

| S5. diuretics and masking agents |

2 (5.3%) | Furosemide |

| S6. Stimulants | 1 (2.6%) | Amfetamine, Dimethylamphetamine |

| S8. Cannabinoids | 3 (7.9%) | Carboxy- THC |

| S9. Glucocorticoids | 3 (7.9%) | prednisolone |

A cross-sectional survey conducted in Kuwait among 194 male fitness center attendees in ten fitness centers revealed that 22.7% were using AAS, with an age range of 19 to 25 years old [15]. This rate parallels the AAS percentage among Saudi Arabia’s athletes, which was reported as 24.5% in 2017 and elevated to 29.3% in 2019 [16]. In the AAF samples, AAS agents like metenolone, drostanolone, boldenone, nandrolone (19-nortestosterone), oxandrolone, metandienone, and 1-testosterone were found. Testosterone and boldenone are the most predominant agents used, similar to other countries such as Spain [15]. Furthermore, male athletes are more likely to use these agents than female athletes [16]. Substances from S1.2. Other Anabolic Steroids were found in 12.8% of the AAF samples and they were SARMs enobosarm (ostarine), SARMs RAD140, SARMs LGD-4033 (ligandrol), SARMs S4 (andarine), and clenbuterol. Despite the initiation of peptide and growth hormone doping in the early 1980s, which are under class S2, only Erythropoietin (EPO) has been detected with a low percentage around 7.7% in the AAF samples [17]. The low percentage is attributable to the limitations imposed on physicians regarding prescribing these hormones in Kuwait for needed patients. Indeed, only one AAF sample identified a prohibited substance under S3.

Beta 2 Agonists class, which is Terbutaline. Terbutaline is the most often detected substance from this class globally, as it enhances power production by increasing glycogenolysis and glycolysis in skeletal muscles [12]. regarding substances under S4. Hormone and Metabolic Modulators, only two AAF samples contained substances from this class, and these are letrozole and meldonium. Similar to that, only 2 AAF samples (5.1%) detected a substance from S5. Diuretics and Masking Agents class, specifically furosemide. Moreover, the study showed that two prohibited substances from S6. Stimulants class, which are detected in 2 AAF samples (5.1%). These are amfetamine and dimethylamphetamine and they are retrospectively classified as specific and non-specific stimulants. The distinction between them lies in the fact that the specific stimulants typically have narrow, more targeted pathways in the brain, whereas non-specific stimulants operate through broader pathways in the brain. [2,12,18]. in addition, Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is the only substance under S8 Cannabinoids class, is present in 3 AAF samples (7.7%). Although it’s considered a social drug, it enhances the athlete’s performance by mood-altering, focus, perception, and pain-relieving effects. It is considered the most frequent substance detected globally under this class [3,12]. An Italian study indicated that 18% of AAF cases were for cannabis, with athletes reporting its use as a social drug rather than for performance enhancement [19]. Research conducted in the USA investigated that the most prevalent prohibited substance used among USA’s athletes is cannabis, with a prevalence of approximately 4.2%[4]. the second most common substance in S9 Glucocorticoids class is prednisolone. It can enhance performance by reducing inflammation, improving recovery, and masking pain. In addition, it treats several medical conditions due to its anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, and immunosuppressive effects. The athlete's diagnosis of Crohn's disease led to the retroactive detection of prednisolone in two of the three AAF samples.

One of the main objectives of this study is providing recommendations to improve the antidoping program in Kuwait, which should be at athlete, agency, and country levels. The improvement requires a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach that addresses education, enforcement, research, and collaboration. Below are specific recommendations for each level to enhance anti-doping efforts and provide a culture of clean sport. Establishing a mandatory, age-appropriate education program on antidoping for athletes across all age categories, especially those aged 16 years to less than 30 years old. This age category is significantly affected by external factors that propel them toward doping due to their low educational level, insufficient awareness of consequences due to violations of anti-doping rules, and financial support [7,10]. The education program should address the importance of fair competition, legitimate methods to enhance performance and muscle development, and the mechanisms of the antidoping process. In addition, it should elucidate the rights and obligations of athletes to antidoping programs. Furthermore, the program must impart sufficient knowledge concerning prohibited substances, their doping effects, and associated health risks. Certain athletes utilize supplements to enhance performance and muscular development, which are readily obtainable without a medical prescription. But they didn't know that some supplements aren't approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and may contain illegal substances, either on purpose or by accident.

This is especially true for synthetic stimulants and anabolic substances [20-23]. Because of that, athletes need guidance on supplement choices and side effects. Establishing accessible and transparent communication channels between athletes and KADA can accomplish this, enabling athletes to verify substances prior to usage. The FDA and WADA must conduct the verification using valid websites. The educational program must also provide athletes with a valid approach to apply for TUE if they are using prohibited substances for legitimate medical reasons. They must understand the procedure and the importance of transparency. Not only athletes, coaches, managers, and support staff should also receive an education on anti-doping to better recognize the pressures participants encounter and offer assistance in making ethical decisions. A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia revealed that 46.1% of athletes utilized AAS following recommendations from their coaches [24]. Additionally, a systematic review identified various factors contributing to doping in sports, highlighting that athletes operate within a broader, complex sports system, which includes governance, policymakers, clubs, team members, sponsors, and support staff. It identified that the coach and coach-athlete relationship represent significant factors influencing the athlete’s decisions regarding doping [25].

Since KADA is responsible for detecting and controlling doping in Kuwait, it should improve testing methodologies to detect new prohibited substances and methods by increasing the number of targeted tests, ABPs, out-of-competition setting tests, and random tests. These various tests will result in more efficient and effective testing methodologies. In addition, the agency should monitor the athletes’ adherence to anti-doping regulations and establish systems for athletes, coaches, or other stakeholders to report suspected doping violations confidentially and without fear of retaliation. Additionally, it must enforce clear, consistent, and fair penalties for doping violations and collaboration with WADA. Moreover, KADA should establish a research department, which should be responsible for conducting research in the field and encouraging the exchange of research, data, and resources among anti-doping agencies to remain updated on evolving doping practices and detection techniques. This research can provide effective recommendations that can help in the improvement of the antidoping program and maintain effectiveness.

Kuwait is one of the pioneering countries in promoting clean sports free from doping since the establishment of KADA. It surmounts all obstacles to facilitate the agency’s tasks and guarantee its sustainability. However, KADA still necessitates the collaboration of multiple institutions and ministries inside the country to successfully implement the anti-doping program. The Kuwait General Administration of Customs is the first in line, responsible for inspecting all imported materials and dietary supplements from outside the country and regulating their sources. It can assist by monitoring these supplements that contain prohibited substances and reporting them. In addition, one of the key ministries that play a crucial role is the Ministry of Health. It is responsible for raising awareness among healthcare professionals about the latest updates in anti-doping policies and the prohibited list, enabling them to identify illegal use by athletes. Furthermore, KADA requires direct collaboration with the Drug Regulatory Department, which is responsible for inspecting various pharmaceutical products and dietary supplements available in the country. This department serves as an independent third party, assisting in the evaluation of dietary supplements and ensuring their compliance with FDA and WADA regulations regarding prohibited substances. Additionally, physicians, pharmacists, and laboratory technicians can contribute to the enhancement of anti-doping policies and provide educational materials to athletes, as they are the experts in the field. KADA could also work with the Public Authority for Sport to bring the Medical Sport Centre roles to life by opening sports medical clinics where athletes from all sports can get medical advice on their health and the use of supplements. These clinics may provide consultations in person or online through official platforms.

Indeed, KADA requires joint efforts with the Ministry of Information, the Ministry of Education, and the Public Authority for Sport to develop different anti-doping awareness programs using the media, which is considered a potent instrument globally. It is also recommended to coordinate and participate in different public campaigns at public venues, schools, universities, and other locations to elevate awareness among athletes and the community. It is also necessary to study the impact of these awareness programs and campaigns to improve and update them. Furthermore, KADA can use its website and social media platforms to promote its anti-doping program, ensuring accessibility to the public.

The study initially analyzed the prevalence of prohibited substance usage based on several factors. It provides details regarding the prohibited substances detected in the AAF sample. In addition, it provides comprehensive recommendations to improve antidoping programs at various levels. In contrast, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the number of samples is considered insufficient; they constitute only 2.4% of the total 27000 athletes registered with various national federations and clubs in Kuwait, as reported by the Public Authority for Sport in Kuwait. This leads to underestimating the prevalence of prohibited substance usage among athletes. Due to the varying half-life of the prohibited substances, the prevalence of AAF in urine and blood samples may be underestimated. As a result, some samples were collected out of the time window of the presence of prohibited substances or their metabolites in the samples [21]. Consequently, the negative results may not be absolutely accurate due to the timing of sample collection from athletes. Secondly, not all sports disciplines are subjected to the doping testing process, which includes equestrian, heji, motorsport, mind sports, baseball, karting, and pigeon and bird sports.

Additionally, the doping testing processes do not include badminton, cricket, diving, lifesaving, air sports, and modern pentathlons. Thirdly, there is insufficient information regarding the educational levels of athletes and their consumption of supplements and their sources. This information could facilitate an investigation of their effects on doping practices among athletes in Kuwait. Fourthly, there is insufficient information concerning the reasons behind doping and the sources of prohibited substances among athletes with AAF samples. Fifthly, fewer samples were collected from females rather than males, resulting in unequal sample sizes between the two groups. That leads to it being statistically difficult to compare prohibited substance utilization based on gender.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the prevalence of prohibited substance usage among athletes in Kuwait highlights a pressing issue that requires immediate attention. The results underscore the need for enhanced awareness, stricter enforcement, and improved antidoping programs to combat this challenge. While the study provides valuable insights into the factors influencing doping practices, it also identified several areas for improvement, including establishing educational programs and providing support for athletes. Addressing these issues through comprehensive recommendations at the levels can help to promote a safe and justice sport environment.

Declaration

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was taken from the ethical committee under the head of KADA administration to use data from ADAMS for research purposes, and informed consent to participate was not needed for this study.

Consent for publication

KADA administration approved for publication and that is documented with the ethical approval form.

Data Availability

The data used to support the results of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding for conducting this study.

Authors Contribution

The main author is responsible for data analysis and writing the manuscript, while the co-author is responsible for data collection processes and revising data.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to KADA for acceptance of using the test results obtained from doping controls performed in Kuwait.

References

- Hurst, Philip. "World anti-doping agency." Routledge Handbook of Applied Sport Psychology: A Comprehensive Guide for Students and Practitioners (2023).

- World Anti-Doping Agency. Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report (2022).

- Davoren, Ann Kearns, Kelly Rulison, Jeff Milroy and Pauline Grist, et al. "Doping Prevalence among US Elite Athletes Subject to Drug Testing under the World Anti-Doping Code." Sports Med 10 (2024): 57.

- World Anti-Doping Agency. Copenhagen Declaration List of Signatories (2021).

- Kuwait Anti-Doping Agency. Background—Kuwait Anti-Doping Agency (2024).

- Aljaloud, Sulaiman O., Khalid I. Khoshhal, Abdullatif A. Al-Ghaiheb and Mohammed S. Konbaz, et al. "The prevalence of doping among Saudi athletes: Results from the National Anti-Doping Program." J Taibah Univ Med Sci 15 (2020): 19-24.

- Collomp, Katia, Magnus Ericsson, Nathan Bernier and Corinne Buisson. "Prevalence of prohibited substance use and methods by female athletes: Evidence of gender-related differences." Front Sports Act Living 4 (2022): 839976.

- Strano Rossi, Sabina and Francesco Botrè. "Prevalence of illicit drug use among the Italian athlete population with special attention on drugs of abuse: A 10-year review." J Sports Sci 29 (2011): 471-476.

- Terreros, José Luís, Pedro Manonelles and Daniel López-Plaza. "Relationship between doping prevalence and socioeconomic parameters: An analysis by sport categories and world areas." Int J Environ Res Public Health 19 (2022): 9329.

- Aguilar, M., J. Muñoz-Guerra, Plata MdM and J. Del Coso. "Analysis of the doping control test results in individual and team sports from 2003 to 2015." (2018).

- Oleksak, Patrik, Eugenie Nepovimova, Marian Valko and Saleh Alwasel, et al. "Comprehensive analysis of prohibited substances and methods in sports: Unveiling trends, pharmacokinetics and WADA evolution." Environ Toxicol Pharmacol (2024): 104447.

- Al-Harbi, Fares F., Islam Gamaleddin, Ettab G. Alsubaie and Khaled M. Al-Surimi. "Prevalence and risk factors associated with anabolic-androgenic steroid use: A cross-sectional study among gym users in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia." Oman Med J 35 (2020): e110.

- Al Ghobain, Mohammed. "The use of performance-enhancing substances (doping) by athletes in Saudi Arabia." J Family Commun Med 24 (2017): 151-155.

- Alsaeed, Ibrahim and Jarrah R. Alabkal. "Usage and perceptions of anabolic-androgenic steroids among male fitness centre attendees in Kuwait-a cross-sectional study." Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 10 (2015): 1-6.

- García-Arnés, J. A. and N. García-Casares. "Doping and sports endocrinology: Anabolic-androgenic steroids." Rev Clin Esp 222 (2022): 612-620.

- Al Bishi, Khaled Abdullah and Ayman Afify. "Prevalence and awareness of Anabolic Androgenic Steroids (AAS) among gymnasts in the western province of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia." Electro Physician 9 (2017): 6050.

- Holt, Richard IG and Ken KY Ho. "The use and abuse of growth hormone in sports." Endoc Rev 40 (2019): 1163-1185.

- Boghosian, Thierry, Irene Mazzoni, Osquel Barroso and Olivier Rabin. "Investigating the use of stimulants in out-of-competition sport samples." J Anal Toxicol 35 (2011): 613-616.

- Bird, Stephen R., Catrin Goebel, Louise M. Burke and Ronda F. Greaves. "Doping in sport and exercise: Anabolic, ergogenic, health and clinical issues." Annal Clin Biochem 53 (2016): 196-221.

- Lauritzen, Fredrik. "Dietary supplements as a major cause of anti-doping rule violations." Front Sports Act Living 4 (2022): 868228.

- Savino, G., L. Valenti, R. D'Alisera and M. Pinelli, et al. "Dietary supplements, drugs and doping in the sport society." Annali di Igiene, Med Preventiva e di Comunità 31 (2019).

- Helle, Christine, Anne Kristi Sommer, Per Vidar Syversen and Fredrik Lauritzen. "Doping substances in dietary supplements." Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen (2019).

- Van der Bijl, Pieter. "Dietary supplements containing prohibited substances: A review (Part 1)." S Afr J Sports Med 26 (2014): 59-61.

- Alrehaili, Bandar D., Samar F. Miski and Fahad M. Alzahrani. "Assessing the prevalence and knowledge of anabolic steroid use in male athletes in Al Madina Al Munawara, Saudi Arabia." Saudi Med J 45 (2024): 731.

- Naughton, Mitchell, Paul M. Salmon, Hugo A. Kerherve and Scott McLean. "Applying a systems thinking lens to anti-doping: A systematic review identifying the contributory factors to doping in sport." J Sports Sci 43 (2025): 8-22.

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Author Info

1Co-Chairman of the Initial Result Management Committee in the Kuwait Anti-Doping Agency (KADA), Kuwait2The Director General of Kuwait Anti-Doping Agency (KADA), Kuwait

Received: 12-May-2025, Manuscript No. Jsmds-25-165464; Editor assigned: 14-May-2025, Pre QC No. p-165464; Reviewed: 27-May-2025, QC No. Q-165464; Revised: 02-Jun-2025, Rev Manuscript No. R-165464; Published: 10-Jun-2025

Citation: AL-Shemali, Hanan and Nadia AL-Shemali. "Prevalence of Adverse Analytical Findings (AAF) Among Athletes in Kuwait (2022-2023): Results from the Kuwait Antidoping Program." J Sports Med Doping Stud 15 (2025): 413.

Copyright: © 2025 AL-Shemali H, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.